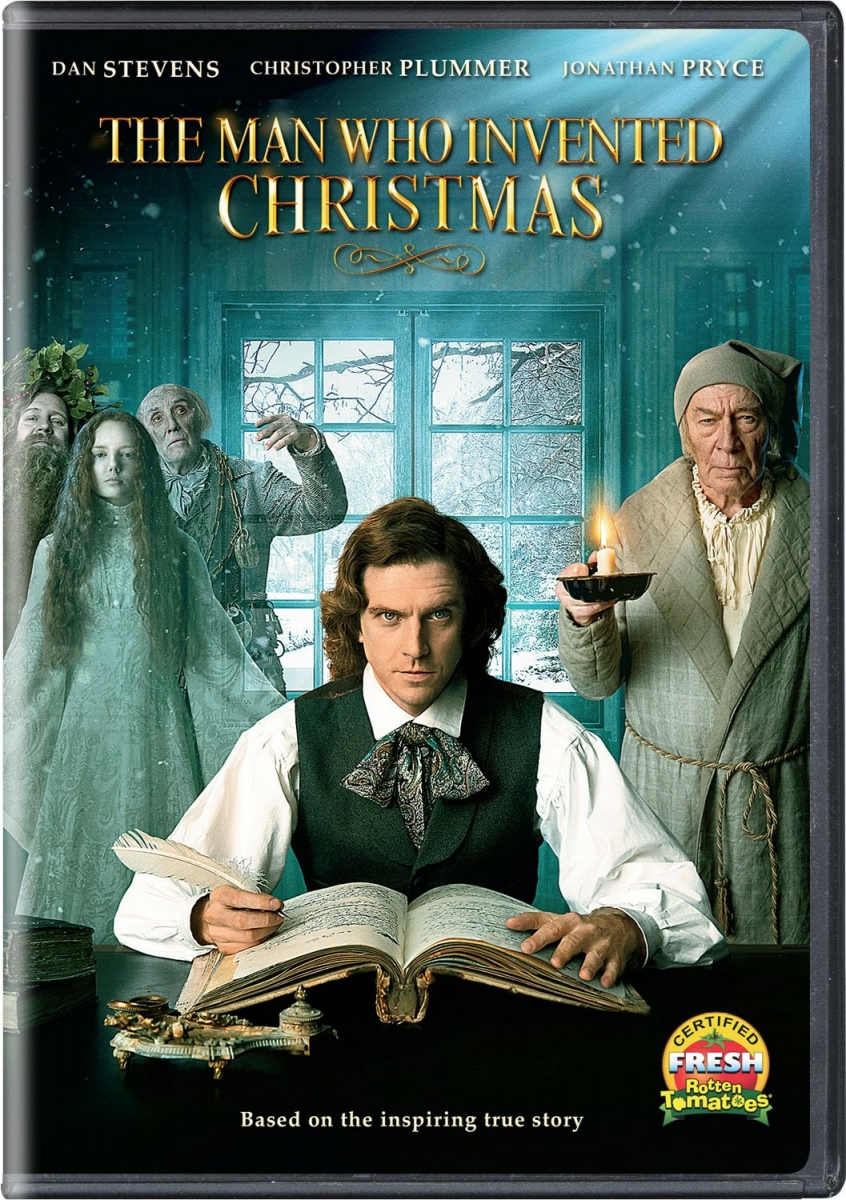

One of my new favorite holiday movies is The Man Who Invented Christmas (2017), which is based on the book of the same title by Les Staniford. Not only does it provide an entertaining perspective on the classic, A Christmas Carol, published in 1843 by Charles Dickens, but crucial to the plot is the story of book production in nineteenth-century Victorian England.

Cover art of DVD--The Man Who Invented Christmas

Early in the film, Dickens and his friend and future biographer, John Forster, visit the publishers Edward Chapman and William Hall (firm name of Chapman and Hall), who had published Dickens’ early books. Here, Dickens pitches them a new one, which will be a Christmas book, and it needs to be available in bookstores prior to December 25. Since it is October of 1843, with Christmas just six weeks away, the flabbergasted publishers express that they cannot imagine having the book “illustrated, type set, printed and advertised, and distributed to shops in only six weeks.” Since Dickens has not yet finished writing the story, and all of these book production processes were handled by a combination of mechanized and non-mechanized means at this time, and by different tradespeople, it does seem a feat that this elaborate gift book could be prepared on such short notice.

To propel his writing process, the movie shows the inspirational influence of a family ghost story and the printed penny dreadful, Varney the Vampire, on Dickens. Penny dreadfuls were serialized, cheap literature that appealed to working-class readers. His young Irish maid, Tara, who is apparently fascinated with ghost stories, proclaims that the printed story is “thrilling.” While Varney the Vampire was not actually published until two years later, the film uses this genre to ignite Dickens’ creative process. Dickens often incorporated ghosts into his writing, and you can read about his use of Victorian Gothic themes in his novels here: Charles Dickens, Victorian Gothic and Bleak House by Greg Buzwell.

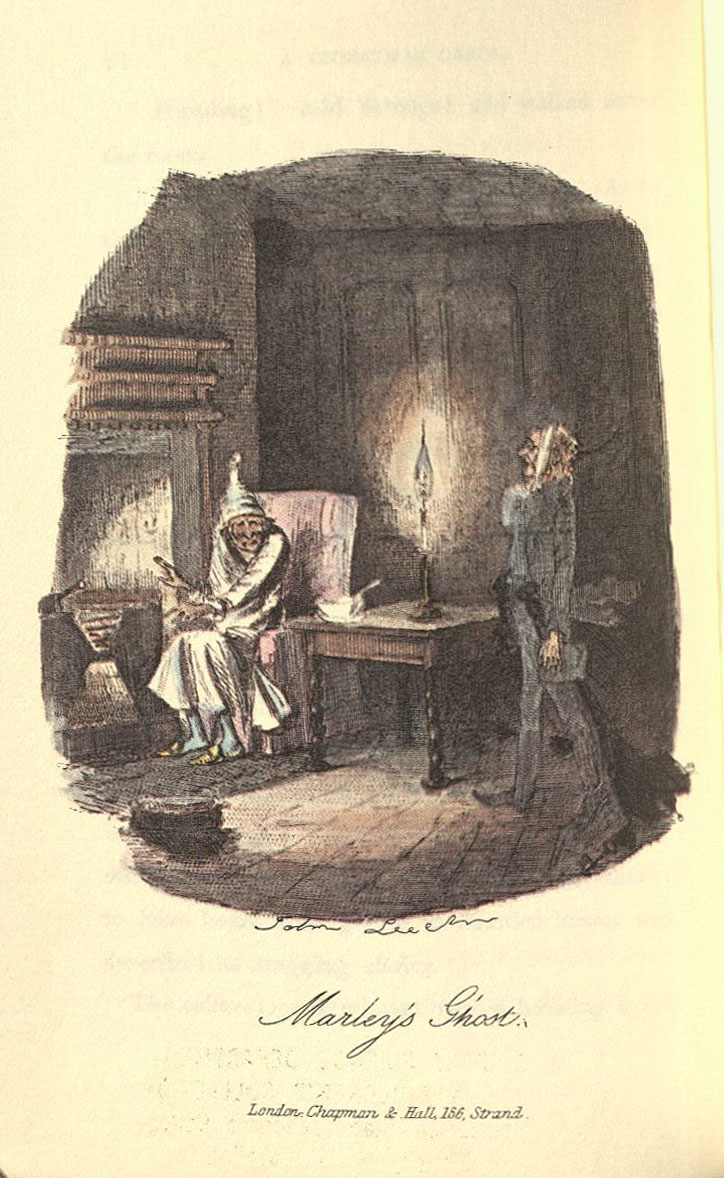

Marley’s Ghost illustration--From a facsimile of A Christmas Carol. Note John Leech’s signature under the engraving. Part of the General Rare Book collection.

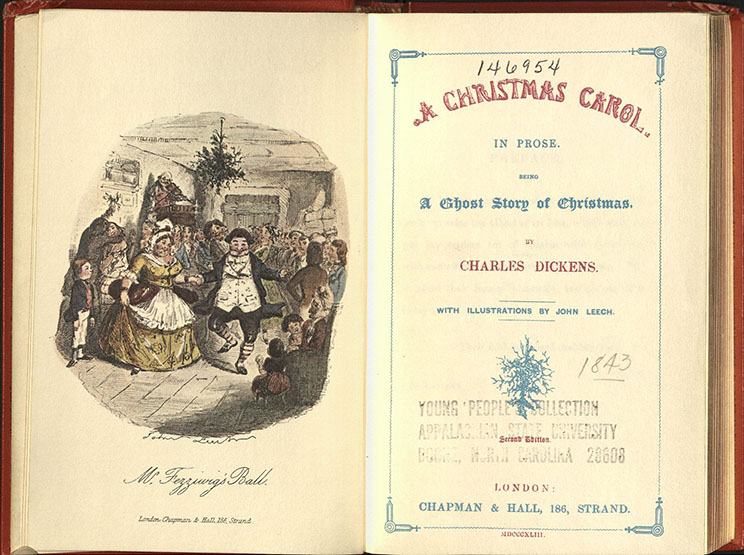

After further developing his story, Dickens meets with the illustrator, John Leech, who created the eight illustrations in the final publication. Since illustrations would take the longest to produce prior to printing, Dickens knew that he had to start here to meet his deadline. In the film, Leech initially refuses to work under such tight time constraints (four weeks at this point), but eventually complies. From his drawings, he creates four, full-page, engravings on plates of steel and four other engravings on wood. Like the drawings, the engraved plates and blocks were also created by hand (meaning, illustration was not a quick process in the 1840s!). The time-saving advantage of the wood engravings was that they could be printed on the same press as the type, whereas the metal plate engravings were printed on a separate press and required additional human power to color with watercolors. Leech obviously had to move quickly to create the images. For additional description about creating the illustrations, plus an analysis of the visual aspects of A Christmas Carol, see Michael Hancher’s “Reading the Visual Text: “A Christmas Carol.”

Dickens title page spread--A facsimile of A Christmas Carol, with a hand-colored illustration by John Leech and the title page. Part of the General Rare Book collection.

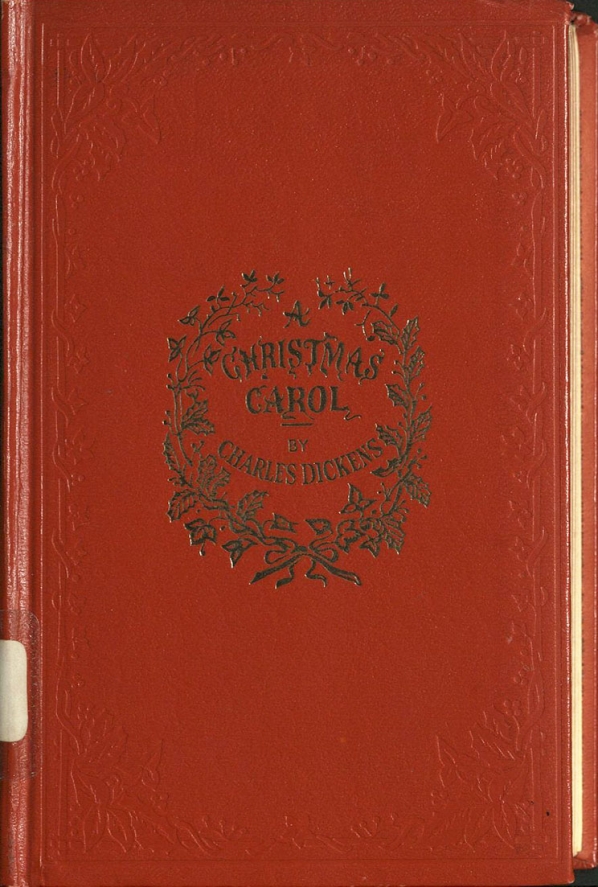

In the film, Dickens also specifies his preferred binding, with details about gilt decoration and green endpapers, to illustrator Leech. I think that it is safe to say that Leech had his hands full with the illustrations and did not also create the binding, especially since it was typical at this time for binders and illustrators to be separate trades. What is not included in the movie is the frequent interaction that Dickens probably had with his binder, since, among other points, his initial desire for green endpapers faded (literally) as he was not satisfied with the look or the product prior to final production. See this description from Bauman’s Rare Books, Christmas Carol First Edition - Charles Dickens, for more details.

![[binding paragraph] Dickens cover--A facsimile of A Christmas Carol’s cover, with gilt. Part of the General Rare Book collection.](https://collections.library.appstate.edu/sites/default/files/dickens_carol_cover.jpg)

Dickens cover--A facsimile of A Christmas Carol’s cover, with gilt. Part of the General Rare Book collection.

After Dickens feverishly finishes his last stave, we see him visit the printer’s shop to beg for the ending to be added to the book. Dickens’ printers were William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans (firm name Bradbury and Evans), who ran a productive shop. We know this, because in 1833, “they installed a large, steam-driven cylinder press of the latest design, made by Middleton & Co., well suited for the demanding printing requirements of newspapers and periodicals. This and some twenty smaller machines were kept running round the clock six days a week, with men working in relays, thus achieving a level of productivity that soon gained Bradbury and Evans a reputation as one of the most efficient printing firms in Britain.” (“Bradbury, William, 1800-1869,” entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). So, while the printer shown in the film, like Leech, expressed dismay in the very short deadline, it is likely that this print shop was able to handle it.

Finally, Hatchard’s, the bookstore that the film shows advertising and selling the first edition of the novel, was founded in 1797 and is currently the oldest bookshop in the United Kingdom. It is likely that Dickens’ work was sold here, as well as in other bookshops in London. To see Dickens’ expenses and profits for this book, see A Christmas Carol Expenses on David A. Perdue’s “The Charles Dickens Page.” We do know that his works were quickly pirated and unauthorized copies sold without his permission, however. Even in the film, he is shown with his solicitor, Thomas Haddock, discussing his case about copyright infringement of Oliver Twist. For more about Dickens’ battle with copyright infringement, especially in America, see Chapter 9, “American Bookaneers,” in Printer’s Error: Irreverent Stories from Book History by J.P. Romney and Rebecca Romney.

Dickens, with significant help from members of the nineteenth-century English book trade (publishers, papermakers, type founders, illustrators and engravers, printers, binders, and booksellers), managed to realize his dream of presenting a Christmas gift book for sale before Christmas (December 19, 1843, to be precise). A Christmas Carol sold its first publication of 6,000 copies before Christmas, and it has been reprinted, read before audiences, broadcast on the radio, and dramatized in movies ever since. The Man Who Invented Christmas provides a delightful peek into writing and publishing in 1840s England.

A selection of additional resources:

The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster (1874)

The Letters of Charles Dickens edited by Madeline House & Graham Storey (1965-)

Charles Dickens and His Publishers by Robert L. Patten (1978)

The Man Who Invented Christmas by Les Staniford (2008)

“The Story Behind A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens” by Rebecca Romney: https://www.baumanrarebooks.com/blog/story-behind-christmas-carol-charles-dickens/

By Greta Browning, Reference Archivist/Librarian and Curator of the Rhinehart Rare Book Collection