This post was originally published on October 15, 2018.

With fall descending on western North Carolina, it is time for chilly evenings, hot cider, and tales of the supernatural. After having laid dormant, buried, and forgotten, the Blog-able Balladry series re-emerges from its tomb to feature a rare ballad perfect for those in search of a Gothic, autumnal tale.

A Rare Ballad

“My fingers began to tremble as if we had indeed discovered fine gold.” — Dr. W. Amos Abrams

On August 26, 1945, Dr. W. Amos “Doc” Abrams and his young protégé, Cratis Williams, took their search for balladry to the home of Uncle Pat Frye, a singer of traditional songs living in East Bend, Yadkin County, North Carolina. At the time of their visit, Frye, who had lived most of his life as a tobacco farmer and miller, was 73 years old and had been blind for several years. Frye’s repertoire of ballads, both British and American in their origin, was vast and included such songs as “The Seventh King’s Daughter” — a variant of the fairy ballad of “The Lady and the Elfin Knight” — and “The Lazy Farmer Boy” — a lyrical admonishment of sloth.

After singing several ballads for his visitors, Frye began to hum a melody which arrested the attention of the collectors. Williams instantly recognized the “The Suffolk Miracle,” an old British ballad of which a complete version had never previously been found in North Carolina. At Williams’ urging, Frye agreed to sing the song in full as Abrams turned on his recording machine. Abrams later recalled: “My fingers began to tremble as if we had indeed discovered fine gold.”

The record label of “The Suffolk Miracle” as sung by Pat Fry[e], AC.102: Cratis D. Williams Papers, W.L. Eury Appalachian Collection, Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina, 28608. Click here to listen to Pat Frye’s performance of the song.

Doc Abrams may have been trembling with excitement at the discovery of “The Suffolk Miracle,” but a close listen to the ballad and a glance at its lyrics will certainly provide its audience with shivers of a different kind. Categorized by ballads scholar Francis James Child as Number 272 in his collection of English and Scottish balladry, the song goes by a variety of names such as “The Holland Handkerchief” or “The Lover’s Ghost.” Pat Frye volunteered the decidedly non-spooky titles “The Richest Girl in Our Town” or “Lucy Bound” for the variant learned from his mother and which he recorded for Abrams and Williams.

A Supernatural Story

“If this ain’t a warning for old folks still

Never hinder young ones from their will.”

— “The Richest Girl in Our Town” as sung by Uncle Pat Frye, August 26, 1945.

The ballad begins by describing the ill-fated courtship of “the richest girl in our town” with “the nearest man.” The girl’s father, disapproving of the relationship, sends her away:

He sent her off full forty miles

To stay 12 months and a day…

One night just before going to bed, the girl hears her lover’s voice and runs outside to find him waiting for her on horseback:

She dressed herself in her richly tire

To ride behind her hearts desire

As she got up behind him

They rode more swifter than the wind

As they rode apon thar way

She kissed his lips

As cold as clay…

Stopping near a tavern, the returned lover complains of a headache to which the girl responds by wrapping his head with her handkerchief.

As they rode to the tavern gate

He did complain how his head did ache

There was her handkerchief

She pulled it off

And bound his head…

The lover then drops the girl off at her father’s home:

Saying get thee down

Go safe to bed

And I will see

Those horses fed….

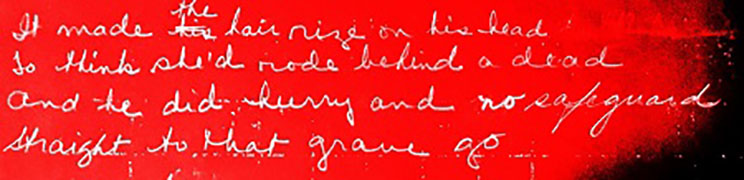

Knocking on the door she meets her father and tells him that her lover has brought her back from her exile. The father, knowing that her lover had died near the time he sent his daughter away, is terrified and the pair race to a nearby graveyard:

It made the hair rize on his head

To think she’d rode behind a dead

And he did hurry and no safeguard

Straight to that grave go…

Opening the coffin, they find her handkerchief wrapped around the head of the lover’s corpse:

There was her handkerchief for very well knew

For there it hung so plain in view

If this ain’t warning to old folks still

Never hinder young ones from their will

Old World Traditions

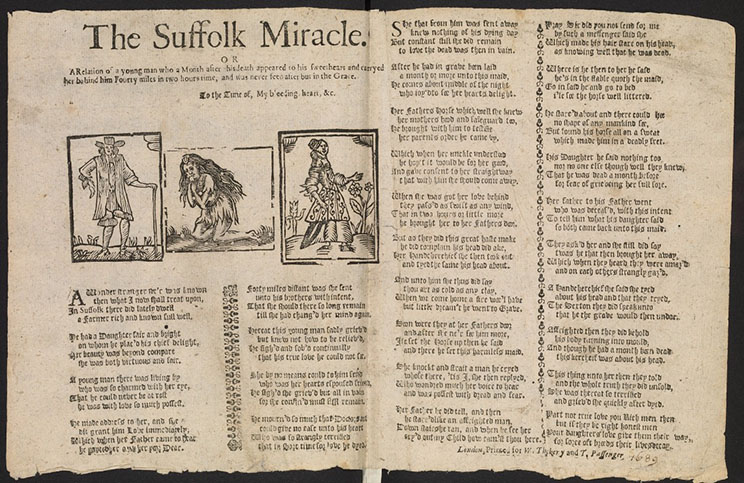

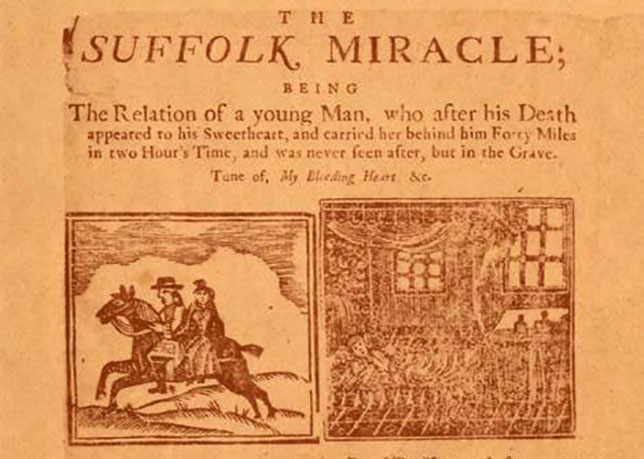

Broadside of “The Suffolk Miracle” Printed for W. Thackery and T. Passenger, 1689. This and other printed versions of the ballad are digitized as part of Ballads Online through Bodleian Libraries at University of Oxford.

Commenting on the ballad “in which the lover comes back out of the grave and takes a sweetheart with him…," Doc Abrams quipped that the story’s denouement was “quite a switch” from the typical ballad story line. Abrams also took time in his spoken notes on his recording of Frye to acknowledge the ballad of “The Richest Girl in Our Town” as “one of the oldest” in its premise. In looking at ballads descended from localities in Europe during the Middle Ages, the narrative of a loved one returned from the grave to visit (or even elope!) with a living companion was not so much a switch on the “usual ballad,” but more of a recurring theme. By the time the “The Suffolk Miracle” or “The Holland Handkerchief” appeared in print in 17th and 18th centuries, the story of a visitor returned from the grave was already part and parcel of European lore. Medievalist Nancy Caciola, in her suitably creepy-titled article, “Wraiths, Revenants, and Ritual in Medieval Culture,” specifically addressed the phenomena of “the undead” in northern European traditions:

Numerous “horror” stories of the undead may be found in chronicles and exempla collections from northern Europe from the late twelfth century on. The tales … about demonically animated revenants are not isolated instances, but part of a longer continuum of stories about reanimated corpses, many of which are told with a high degree of local detail and verisimilitude. In most cases, the dead are presented not as possessed, but as coming back to life on their own. (Caciola, 17)

“The Suffolk Miracle,” broadside printed 1711. Retrieved from Mainly Norfolk: English Folk and Other Good Music

Scholars such as Caciola, in tracing the origins of this recurring instance of the supernatural in early European chronicles, have acknowledged such accounts as being part of the wider canon of revenant stories. These tales of the undead were so much a reality in the Old World that they — like many terrible occurrences — changed language forever. In fact, the skeleton of the French verb, revenir, “to return,” was so shaken by the phenomena that it jumped straight out of its skin to become revenant, a noun that carried the rotted weight of dread and mystery. These medieval horror stories can also be traced further back into Icelandic and Norse traditions, with characters known as draugar, “violent corpses reanimated by their original spirits” who, more often that not, seek revenge on the living (Rollo-Koster, 75).

In the case of both revenants and draugar, the disturbing nature of the stories lie not so much in the initial shock of the undead corpse but in the humanity of its actions. Medievalist Winston Black underlined this point in his chapter, “Animated corpses and bodies with power in the scholastic age,” featured in the volume, Death in Medieval Europe:

Revenants are intelligent imitators of the living: they speak, have emotions, make requests, deliver messages, and even sing. Medieval revenants must also be distinguished, of course, from the resurrected dead: the latter were dead and now alive, while the former are paradoxically both dead and alive, or neither dead nor alive. (Rollo-Koster, 75)

As evidenced above, these examples of the“walking dead” reported in the Old World were not mindless hordes in search of blood and brains. These were individual creatures of the soul, always cognizant of their own existence — whether they were plotting harm to a mortal who had wronged them or returning to show their affection for a lover from beyond the grave. Revenants transcended the supernatural with natural, human elements that thinned the dividing line between spirits that inhabited dead bodies and those already inhabiting living bodies.

The human element of these paranormal tales, mixed with the ballad form’s proclivity for moral storytelling, caused them to reemerge like specters in the New World, defying the expanse of time, generations, and the Atlantic Ocean. When Pat Frye’s singing once again sits the richest girl in town behind her lover’s corpse on horseback, one can imagine that the duo ride through the night not over the rolling meadows of Suffolk but through the foothills of Yadkin County. While Abrams and Williams were sure they had found “The Suffolk Miracle” in August 1945, what Uncle Pat Frye provided them instead was a ballad that — not unlike the dead lover of the song — had returned, a fragment of its former self, wandering in a new landscape.

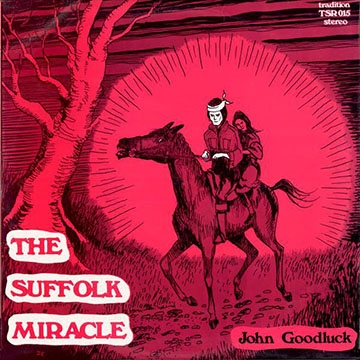

A particularly creepy album cover for The Suffolk Miracle, John Goodluck, Traditional Sound Recordings TSR 015 (LP, UK, 1974). The recording features a traditional English version of the ballad.

The information provided above has only scratched the surface of the lore behind this ballad. Any comments providing additional information related to the above article would be much appreciated.

Header photograph and ballad lyrics from AC. 114: W. Amos Abrams Papers, W. L. Eury Appalachian Collection, Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina 28608.

Sources cited and consulted:

Caciola, Nancy. “Wraiths, Revenants and Ritual in Medieval Culture.” Past & Present 152 (August 1996): 3–45.

Hudson, Arthur Palmer, and Henry M. Belden. Folk Songs from North Carolina. North Carolina Folklore Volume II. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1952.

Rollo-Koster, Joëlle, ed. Death in Medieval Europe: Death Scripted and Death Choreographed. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2017.

--Blog post contributed by Archives Assistant Trevor McKenzie