Hello, Special Collections blogroll readers! This is a guest submission by Ross Cooper, Public Services Associate, a member of the Public Services team staffing the “front end” of our Reading Room and research space.

A colleague came up with the idea of asking each member of our Special Collections team, a group with diverse interests and backgrounds, to ponder what one item held in the archives of the Special Collections Research Center is their favorite—or what single thing they would choose if the Dean of the University Libraries asked us to choose and pull an item to show to visitors (and, also, why).

SARUM RITE MEDIEVAL BOOK OF HOURS LEAVES (My Favorite Things, Part the First)

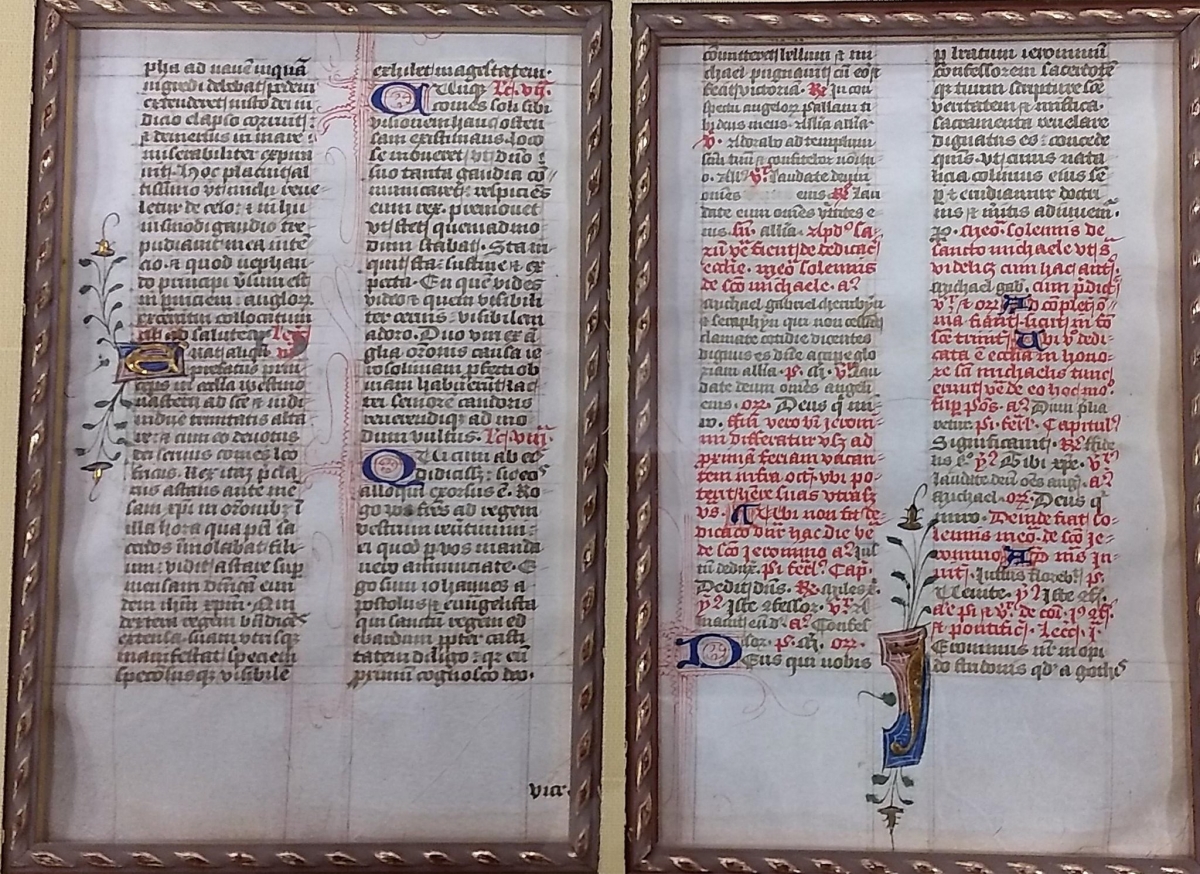

When asked to think about what I would select to show to visitors to the Special Collections Research Center—having to choose only one item—I had to do some thinking and weighing of considerations. My first impulse was to think of what I suppose is my own personal favorite item, consisting of a frame in the anteroom of the Rhinehart Reading Room that holds two small leaves from a liturgical book from medieval England. Viewers can see only one side of each leaf, but what is revealed is exquisite and fascinating: the ancient pages reveal painstaking hand-lettering and manuscript illumination from, probably, either a missal or personal Book of Hours created in the 1200s. (Read more about this artifact here.) Delicate drawings of leaves and flowers, some intricately detailed with gold leaf, and deep blue-violet capital letters are interspersed with the text, which is in two main colors: a somewhat faded once-black ink for the main text, and vibrant red for the rubrics—illustrating the original, literal meaning of “rubrics,” from the Latin for “red [letters]” (rubrica), liturgical instructions or ritual prompts indicated by the use of the red color.

Leaves from a Sarum Rite liturgical book, 13th-century England, Rhinehart Room, Special Collections, Appalachian State University

HOLINSHED’S CHRONICLE (My Favorite Things, Part the Second)

Although this item is intriguing (and I feel a bit overawed when viewing the letters and ornamentation and thinking that the work, attention, and devotion expended on these pages—and doubtless hundreds of others, in the original, complete book—occurred some 800 years ago), I shifted in my thoughts to another work of the art of the book, this one closer to our own times and distinguished from the medieval example by being a product of the revolution brought about by the invention of the printing press: an invention that changed society, education, and religion, in addition to the way of creation and dissemination of books and the ideas they contain.

This is the originally three-volume work titled in full Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande, more commonly known simply as Holinshed’s Chronicles. Despite the common shorthand attribution of the work to Raphael Holinshed, a translator and historical writer active in the London publishing scene in the mid-1500s, the book is a work of collaborative history—a monumental compilation of contributions by various authors to produce a narrative of the principal nations of Great Britain: England, Scotland, and Ireland, each considered individually. (Sorry, Cymru / Wales, the editors lumped the glorious history of Wales into that of paleo-Britain and England). The Chronicles combine mythical history, narrative-building, propaganda, and the perspectives of the individual authors to form a distinctive record of the world of Tudor Britain, encapsulating the self-perception and worldview of its inhabitants (or, more accurately, of some of them).

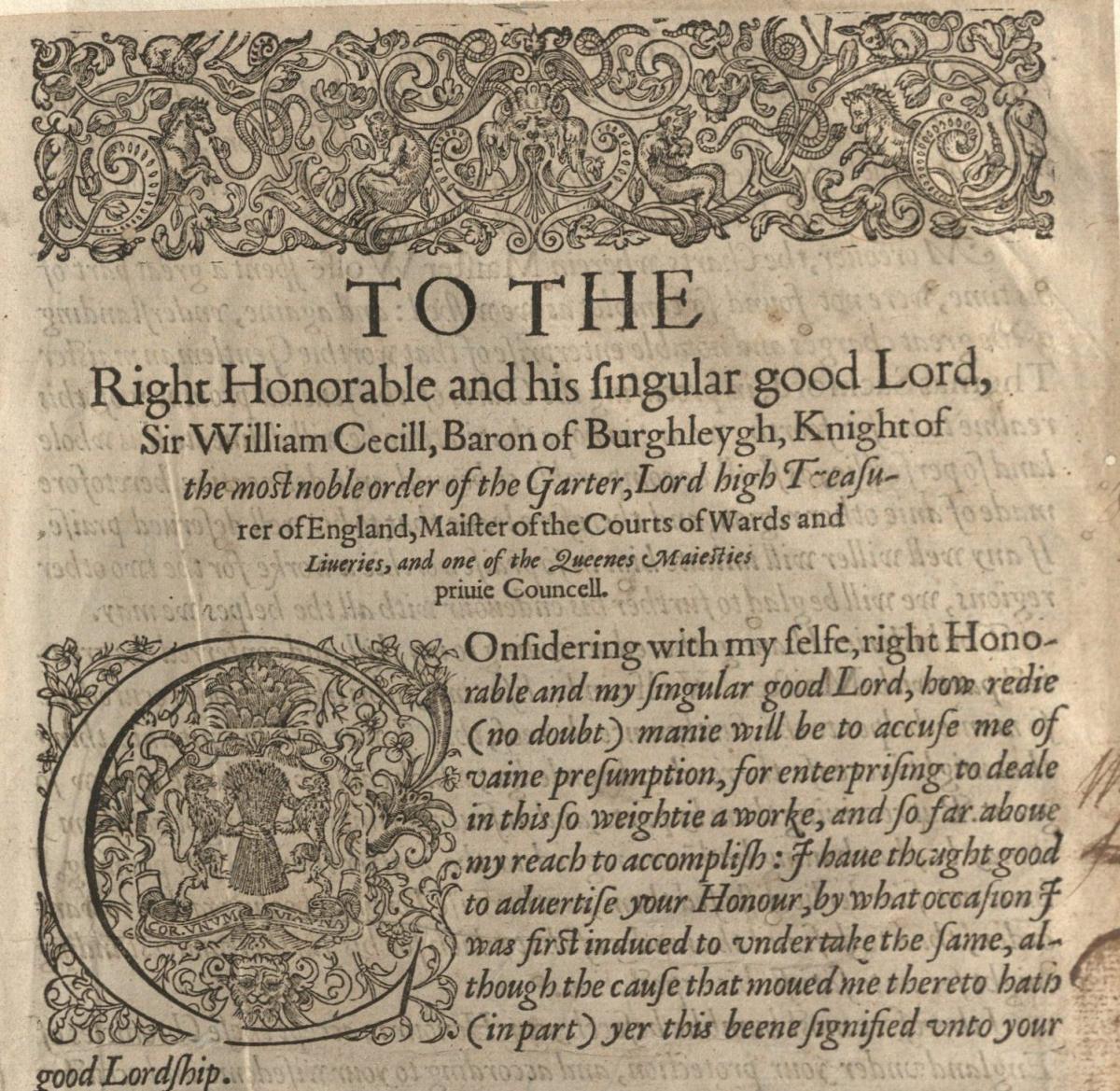

Top of the dedication page of the Chronicles, with printed ornamental capital letter “C” and beginning of the dedication to William Cecil, Lord Burghley (1520–1598), key advisor to Queen Elizabeth I

Special Collections is fortunate to have a full copy (three volumes bound into two, as was done in some original printings) of the second edition of the Chronicles, which was published in 1587, a decade after the original edition appeared in 1577. Although the rarer, earlier edition would also be a prize, the number of extant copies of the original is very small: probably fewer than 200 copies can be found in the world today, and many of those are missing a volume, have had illustrations or other pages cut out, or are in private collections.

The second edition has some substantial differences from the one printed a decade earlier. Of particular interest to scholars of the period and those studying the formation of British identity, the development of historiography (writing about history), and the role of propaganda in the early modern period, the second edition had some sections completely removed (the technical term is the rather unfortunate and visceral word “castrated”), with many pages being excised from the text. The material removed for the 1587 issuance was taken out by the Privy Council of the government of Queen Elizabeth I for a range of reasons, including hesitancy to offend the current King of Scotland, James VI (who later became King James I of England and Great Britain, of Bible translation project fame); concern over offending the hierarchy of the Church in England with biographical details of some of the Archbishops of Canterbury; or accounts in which England’s role and actions on the world scene might have cast the nation and its leaders in a poor or morally questionable light (including the intervention in continental Europe when Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, was sent as an envoy, counselor, and possible conspirator to aid Protestants in the Netherlands seeking self-rule separate from the Empire of Spain).*

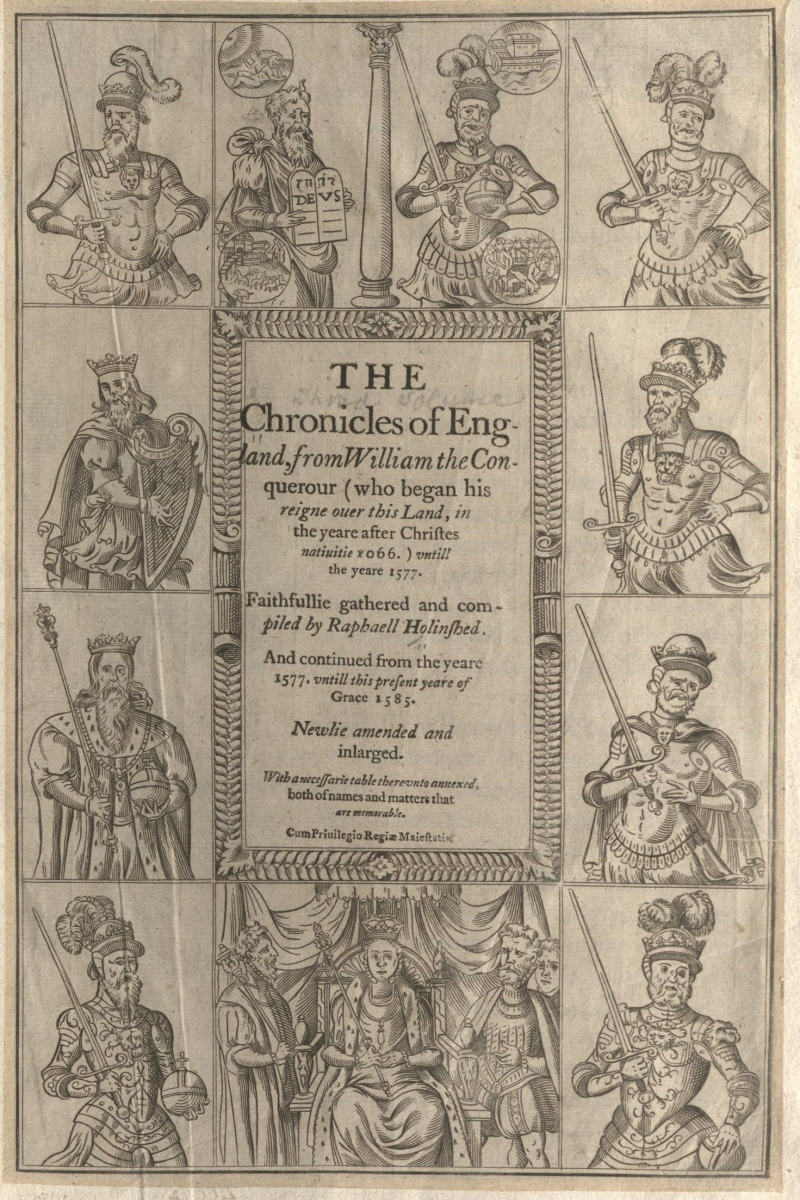

The second edition also had far fewer illustrations in the form of woodcut prints, which had been profuse in the 1577 edition. There is speculation that the removal of most illustrations may have been for more than one reason. The cost of commissioning and printing such images added significantly to the expense of a printed work, and it seems that the company producing the second edition of 1587 may have had reduced funds for their second project. Also, however, it has been suggested that the elimination of illustrations might reflect some anti-image stance of an increasingly militant (and militarily threatened from abroad) Protestant polity. This seems somewhat far-fetched to me, and scholars have reflected that the simple lack of a long history of illustration in historical accounts in the British Isles could also be a plausible explanation. The 1577 edition, along with the perennial bestseller Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (replete with graphic illustrations of martyric violence), were among the first volumes in England to break this pattern, both published within a generation.

One of the few pages in the second, 1587 edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles held in Special Collections that contains illustrations; seen here, figural representations of historical personages on the title page of the “England” volume, Volume I

My own particular interest in Holinshed’s Chronicles stems from two sources: the first personal, the second more broadly “inherited” from my parents. First, when returning to graduate school to seek a degree in library science after a multi-year academic hiatus, one of the classes I took as an elective was a course in archiving. The course instructor was Dr. Hal Keiner, at the time the University Archivist at Appalachian State University. Following a career as a corporate archivist in New England, Dr. Keiner pursued further archival studies incorporating his passion for and interest in British history as well as the history of the book.

A class project was to pick an item from the Rare Books in Special Collections and prepare a mock-up description and accession or cataloging guide, as if the book were being prepared for addition to the collections for the first time. I chose “Holinshed” due to my second interest (combined with my own 1990s fascination with screen adaptations of Shakespeare’s dramas by Kenneth Branagh and Baz Luhrmann): a longtime amateur interest of my parents—the controversy, theories, and scholarship surrounding the “Shakespeare authorship question.”

The question in question is the consideration of whether the plays, sonnets, and other literary works ascribed by tradition to William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon could have been, or might have been, or almost certainly were, authored by another person (or persons). The authorship question and the often contentious writing, debate, and accompanying acrimony over who did (or did not) write the Shakespeare plays and sonnets goes back centuries— even to the early seventeenth century, several years before the 1616 death of William "Shakspeare" (one of a few extant spellings of his name, written by William of Stratford, or written for him, in a few surviving signatures from legal documents). During the Stratford small-businessman’s life, “[t]he title of a 1611 epigram did so openly and with startling bluntness: addressing ‘Shake-speare’ as ‘our English Terence.’ Terence was an ancient Roman playwright notorious as a suspected frontman for two hidden, aristocratic writers” (The Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship, “Who Wrote Shakespeare? Shakespeare Authorship 101,” retrieved January 30, 2026).

Partisans of one side or the other in the debate have, at times, both acknowledged the fact that whoever was the true author seems almost unmistakably to have used Holinshed’s Chronicles as source material for, in particular, the historical plays about certain kings of England, as well as plays based on figures from a more distant and mythical past, including Macbeth and parts of Cymbeline and King Lear.

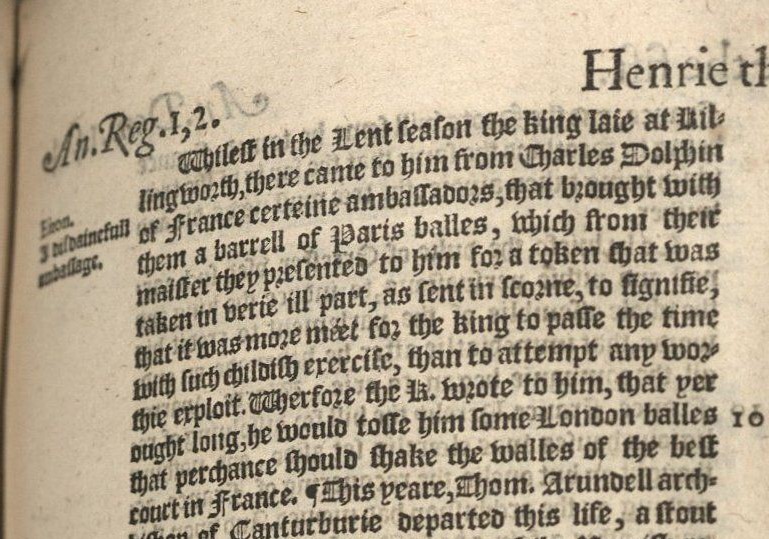

Here is a scan from page 545 (Vol. I, England) of the 1587 edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles with the story of the Dauphin (Prince and Heir Apparent) of France sending a mocking gift of a shipment of tennis balls as “more fitting sport” for the newly ascended King Henry V than battle and attempted conquest of lands claimed by both France and England. A transcription appears below to provide greater readability than the blackface type used in the printing of the day.

The tennis-ball embassy (p. 545)

Exon. A scornful embassage

“Whilst in the Lent season the king lay at Killingworth, there came to him from Charles, Dauphin of France, certain ambassadors that brought with them a barrel of Paris balls, which from their master they presented to him for a token that was taken in very ill part, as sent in scorn to signify that it was more meet for the king to pass the time with such childish exercise than to attempt any worthy exploit [TLN 403–8]. Wherefore the king wrote to him that ere ought long he would toss him some London balls that perchance should shake the walls of the best court in France” [TLN 409–38].

Some readers may have seen the tense unfolding of this scene in the 1989 film adaptation of Henry V by Kenneth Branagh, or in some other production of the historical Shakespearean drama on stage or for the screen. The Holinshed passage includes the use of the anglicized term "Dolphin" for the title 'Dauphin," but this may be simply because the French title itself comes from the word for "dolphin," an early holder of the title having the device of two dolphins on his coat-of-arms.

Although what seems to be a fairly direct incorporation of the telling of a story or historical event in the play is by no means singular proof that the playwright had read Holinshed’s Chronicles, nor of the level of education that the author of Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets may have attained, it does seem likely that the historical compendium assembled by Raphael Holinshed and his colleagues was very much “in the [proverbial] ether” of the Elizabethan age, and that the person behind the pen who created some of the greatest historical dramas of the time (some might argue in all of the English language) drew heavily on this book (or book of books, or “Grace of Books”) for background material.

In several ways, Holinshed’s Chronicles stands at the crossroads of book history, national memory, and literary creation. It embodies the shift from manuscript to print culture, reflects the political and religious tensions of early modern England, and served as a foundational source for some of the most enduring works in the English literary tradition. For Special Collections, the volume is not merely an artifact of the past but a living conduit through which students, researchers, and visitors can encounter the intellectual world that shaped Shakespeare and his contemporaries—making it, to me, an ideal single item to place in a visitor’s hands.

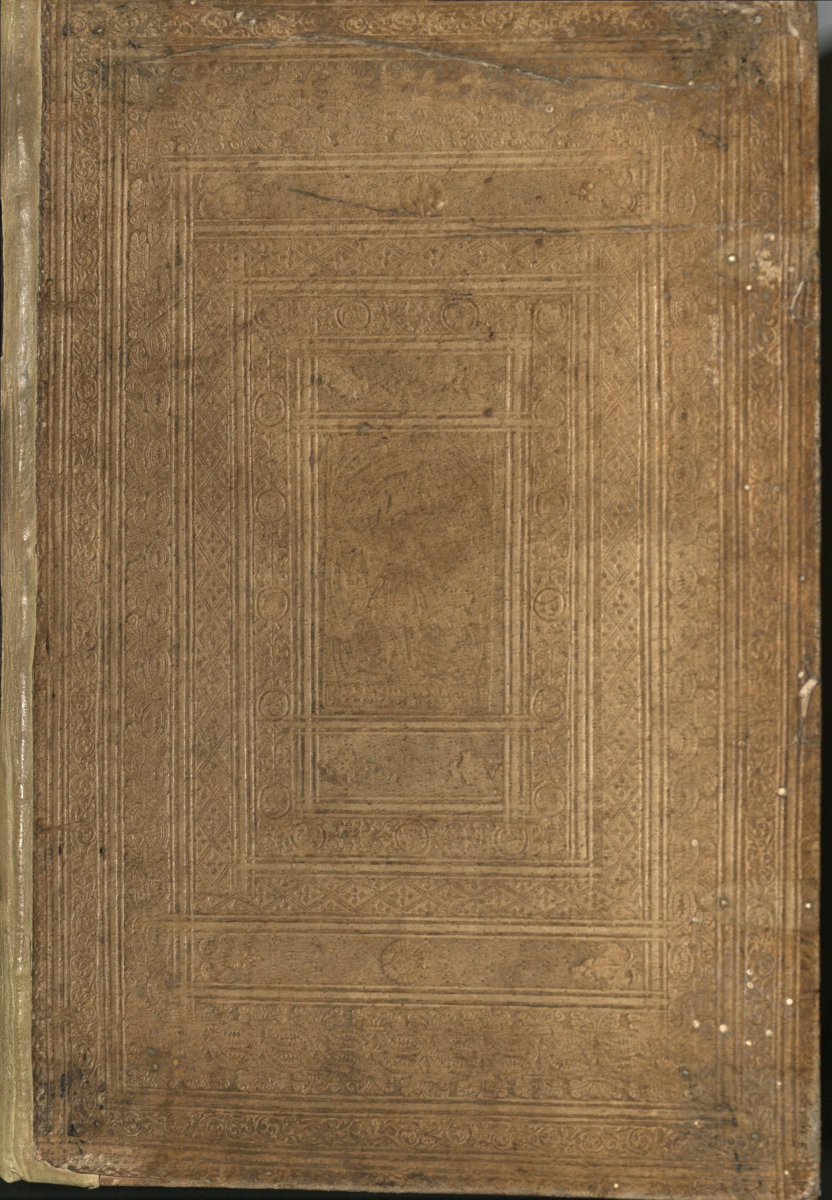

Front cover of the first bound volume of the Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, from the second edition (1587) held in Special Collections.

How exciting might it be for our human imaginations to reflect that, in encountering this volume, we might be seeing, touching, and reading a book that Shakespeare saw, and touched, and read—

Whoever he may have been?  **

**

For Further Reading

Holinshed’s Chronicles, texts online courtesy of Project Gutenberg. Complete digital texts of both the 1577 and 1587 editions in multiple formats.

The Oxford Handbook of Holinshed’s Chronicles, Oxford University Press. Online ISBN: 9780191750533; Print ISBN: 9780199565757. AppState Library catalog record link.

The Castrations of the Last Edition of Holinshed's Chronicle: Both in the Scotch and English Parts, Containing Forty-Four Sheets; Printed with the Old Types and Ligatures, and Compared Literatim by the Original, 1723. Available online via Eighteenth Century Collections Online from Gale (subscription database, available through Appalachian State University).

Works Cited

* William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA website: “The First and Second Volumes of Chronicles.”

** Image, “Shakespeare Candidates1,” courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Pictured, clockwise from top left: Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, Francis Bacon, William Stanley, Earl of Derby and Christopher Marlowe; in the center, the "grotesque portrait," allegedly of William Shakespeare of Stratford-on-Avon, from the First Folio of the Plays. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ShakespeareCandidates1.jpg, retrieved via the internet on February 9, 2926. Smatprt at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons